扩展App Inventor:具有多点触控和手势检测功能

摘要

MIT App Inventor 是一个基于块的事件驱动编程工具,它允许每个人,尤其是新手,开始编程和构建功能齐全的 Android 设备应用程序。与使用 Android Studio 的传统文本编程相比,它的功能有限。我们通过构建扩展组件使 App Inventor 具有多点触摸手势检测功能,例如双指旋转和用户定义的自定义手势。我们的论文说明了组件的实现、组件的示例用法以及它们如何帮助新手构建涉及手势识别的应用程序。

关键词

系统、计算机科学教育、手势识别、多点触摸识别

简介

MIT App Inventor 是一个基于块的事件驱动 Web 平台,它允许每个人,尤其是新手,开始编程和构建功能齐全的 Android 设备应用程序。应用程序不是基于文本的编程,而是通过基于块的可视化编程框架 Blockly 进行编程。App Inventor 应用程序基本上有两个部分:组件和编程块。组件是应用程序可以使用的项目。它可以是手机屏幕上可见的,例如按钮或标签,也可以是不可见的,例如摄像头或传感器。每个组件都有一组块,程序员可以使用它来控制其行为。

图 1. App Inventor 应用程序的模块,当有新消息到达时,该应用程序会自动大声读出文本消息。

图 1 显示了示例应用程序的块,该应用程序在收到新短信时会自动大声朗读短信。程序员无需使用 Android 中的传统 Java 编程来实现事件监听器,只需拖动一个块并在发生特定事件时添加所需的相应操作即可。

与传统的基于文本的编程不同,MIT App Inventor 引入了一种事件驱动的编程模型。“事件”是计算机科学中的一个概念,指的是用户的操作,例如触摸屏幕、单击按钮等。随着移动和网络平台的流行,事件处理正成为一个重要的概念,但它通常在 CS 课程的后期教授。此外,在 Android 开发中使用的某些计算机语言(如 Java)中,很难处理诸如按钮单击之类的简单事件。在 Java 中,程序员需要通过创建监听器来处理事件,这对于新手来说是一个难以理解的概念 [1]。

然而,几乎每部智能手机或平板电脑都有触摸屏。根据 iSuppli 的报告,2012 年全球共售出 13 亿块触摸屏,而 2016 年,全球预计将售出 28 亿块触摸屏 [2]。由于大多数触摸屏都嵌入了多点触摸技术,因此多点触摸事件在我们与智能手机或平板电脑中的应用程序交互中扮演着重要的角色也就不足为奇了。常见的多点触摸事件包括滑动、捏合和旋转。一些应用程序还允许用户定义自己的手势以供以后使用。对于应用程序程序员来说,了解如何正确检测和处理多点触摸事件是必要的,但对于新手程序员来说,使用传统的基于文本的编程语言构建具有此类功能的应用程序通常很困难。

2015 年,App Inventor 拥有来自 195 个国家/地区的约 300 万用户。但是,它不支持允许程序员检测多点触摸事件的功能。在本文中,我们说明了两个扩展组件的实现。第一个组件检测双指旋转,第二个组件使用户能够定义手势并在稍后执行。这两个组件及其块是为新手程序员设计的,可供新手程序员使用。程序员通常需要具有一些 App Inventor 经验,但不需要了解 Java 或 Android 软件开发工具包 (SDK) 库。

本文的其余部分组织如下。第二部分介绍了背景和相关工作。第三部分说明了两个组件的设计和实现细节。第四部分描述了我们使用这两个组件构建的示例应用程序,比较了传统编程和我们的组件的学习曲线,并讨论了它们的局限性。我们最后总结了我们的贡献。

背景和相关工作

在本节中,我们介绍了 App Inventor 扩展,并讨论了使用 Android Studio 实现手势检测的传统方法。最后,我们描述了我们之前构建的用于检测捏合手势的组件。

App Inventor 扩展

App Inventor 是为新手程序员和青少年设计的,是计算机科学的入门课程,因此它支持 Android 应用程序的基本功能,例如按钮、相机等。但是,它不包含与 Android 应用程序接口 (API) 相同的功能集,并且其组件不能根据程序员的特殊需求进行修改。

由于大量用户对新组件的请求,App Inventor 发布了一项名为“App Inventor 扩展”的新功能,该功能允许用户使用 Android API 和 App Inventor 源代码构建自己的组件。新组件完全由用户定义,可以像普通组件一样导入到应用程序中。用户还可以更改现有扩展组件的源代码以满足他们的特定需求。App Inventor 团队还维护了一个公共扩展库来支持一些常见组件,例如图像处理。

我们的旋转检测和自定义手势检测组件也将包含在一个公共扩展库中。用户可以根据需要修改检测行为。

使用 App Inventor 进行手势识别

目前,App Inventor 可以处理包括点击、按压、滚动、滑动和滑动在内的手势,但不支持常见的多点触摸手势,例如缩放和旋转。

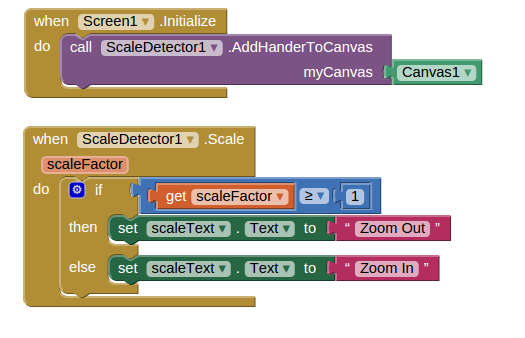

在当前的扩展库中,我们的团队实现了一个“缩放检测器”,它可以处理缩放事件(缩放和捏合)。该组件是使用 Android API 中的 ScaleGestureDetector 类实现的。它计算屏幕上两根手指之间的距离,并返回当前距离与之前距离的比率。如果比率大于 1,则检测器检测到缩小,如果比率小于 1,则检测到捏合。用户只需在知道正在执行哪种手势后注意行为即可。图 2 显示了“缩放检测器”的示例用法,用于更改与比率相对应的文本 [3]。

图 2. 使用比例检测器根据比例修改文本的 App Inventor 应用程序的块。

使用 Android API 进行手势识别

Android API 具有“比例检测器”的内置实现,但它不支持任何旋转检测,因此我们需要实现旋转检测器。详细实现见第 III 节。

对于自定义手势检测,Android API 提供了一个示例应用程序,用户可以使用它来添加用户定义的手势,例如圆形、三角形等。在我们的扩展组件中,我们将直接调用该应用程序来添加手势。该应用程序将手势编码为二进制文件,该文件可由 Android API 中的 GestureLibraries 类读取。读取文件后,所有手势都存储在名为 GestureLibrary 的类中。手势由名为 GestureOverlayView 的类执行,并由与此 View 类关联的侦听器检测。在这个监听器中,输入的手势与 GestureLibrary 中存储的每个手势进行比较,该函数输出一个分数列表,该列表表示输入的手势与库中每个手势之间的相似性。分数越高,相似性越大。程序员可以使用此列表来确定此手势是否是存储的手势之一。一般来说,得分最高的手势就是我们想要检测的手势;但是,如果所有分数都低于程序员设置的最低阈值,则输入的手势不是库中存储的手势之一 [3]。

技术方法

如果熟悉 Java 编程和 Android API,则使用 Android Studio 可以轻松实现手势识别。然而,对于新手程序员来说,情况并非如此,这个过程对他们来说可能令人沮丧和困难。借助 App Inventor 和我们的扩展组件,我们为新手提供了一种简单有效的手势识别方法。

我们构建了两个扩展组件。一个组件检测两指旋转,另一个组件检测自定义手势。它们的工作方式应该与“比例尺检测器”相同,用户只需关注检测结果,而不必关注检测过程。这两个组件都与 App Inventor 中的 Canvas 组件配合使用。

图 3. App Inventor 应用程序的块,允许应用程序用户在画布上画线

Canvas 组件

Canvas 组件是一个触摸感应矩形面板,其大小可由用户定义。Canvas 可以处理应用程序用户的触摸事件,如滑动、向上触摸和向下触摸,以便应用程序用户可以在画布上绘图 [4]。它还包含一组可以以一定速度向某个方向移动的图像精灵。图像精灵的大小、速度和方向可以通过编程更改。图 3 显示了 Canvas 的示例用法。该应用程序允许应用程序用户在画布上画线。图 4 显示了使用 Canvas 对象并允许用户在图像精灵上画线的应用程序的屏幕截图。

图 4. 允许用户在图像精灵上绘制线条的应用程序屏幕截图。

如果程序员向 Canvas 注册了新的事件侦听器,Canvas 还可以在其定义的区域中侦听新事件。新的事件侦听器需要实现 ExtensionGestureListener 接口,并且需要将其添加到 Canvas 的手势侦听器列表中。当发生触摸事件时,Canvas 会遍历所有手势侦听器并执行相应的操作。我们在后面部分中展示的组件使用此功能向 Canvas 添加新的事件侦听器。

旋转检测

双指旋转是一种常见的多点触控手势。它可以用于多种情况,例如旋转 Google 地图以查找某个地方并探索其周围环境,或者在应用程序中旋转图像。

与比例检测不同,Android API 不支持双指旋转,因此我们需要实现旋转侦听器。任务是找到用户旋转手指时的角度,以便我们可以以正确的方向旋转图像。用户每用两根手指触摸屏幕一次,就会形成一条由两根手指组成的线。当用户用两根手指旋转时,又会形成一条新的线,并且之前的线和当前的线之间会有一个角度。图5显示了这个过程。蓝点表示手指在屏幕上的先前位置,红点表示手指的当前位置。两条线之间的角度就是用户旋转的角度。

图 5. 实现旋转手势的思路。蓝点是手指之前的位置,红点是手指当前的位置。旋转的角度是手指形成的两条线之间的角度。

我们使用的角度以度为单位,范围从 -360 度到 360 度。角度的符号表示旋转的方向。正角度表示顺时针旋转,负角度表示逆时针旋转。

我们使用 Android API 中的 MotionEvent 类来检测手指的触摸和移动。第一个手指的位置由 $MotionEvent.ACTION_DOWN$ 事件记录,第二个手指的位置由 $MotionEvent.ACTION_POINTER_DOWN$ 事件记录。这些事件还为手指分配不同的 ID,以便以后区分它们。当手指移动时,会调用 $MotionEvent.ACTION_MOVE$ 事件,并根据它们的 ID 记录两个手指的当前位置。我们可以使用当前位置和之前的位置来计算旋转的角度,并告诉程序检测到旋转手势。此函数返回角度。

我们在测试组件时发现的一个值得注意的问题是 $MotionEvent.ACTION_MOVE$ 太敏感了。手指的微小移动都会触发此事件,因此即使我们不想这样做,它也会检测到旋转。为了解决这个问题,我们在检测到 $MotionEvent.ACTION_MOVE$ 时添加了一个缓冲区,这样我们只会在两个手指的位置变化超过某个阈值时触发“旋转”。

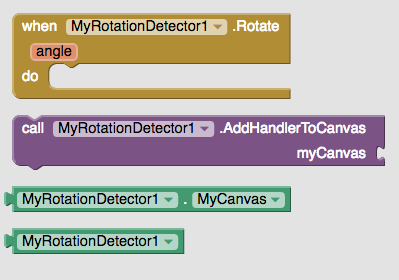

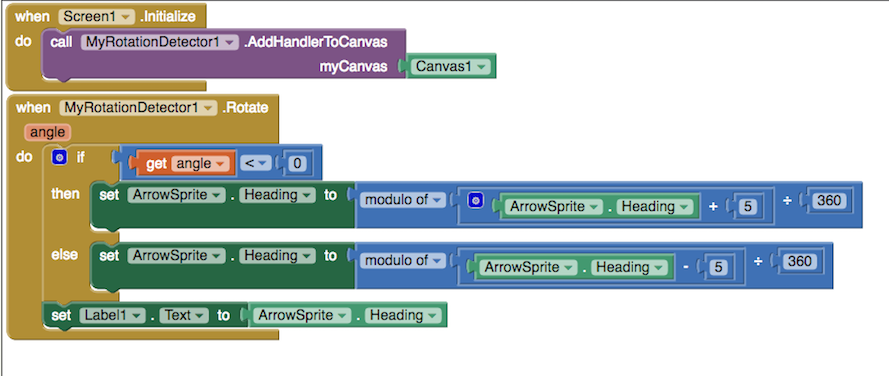

图 6. 为旋转手势组件设计的块。函数 AddHandlerToCanvas 将检测器附加到画布组件,当检测到旋转手势时触发函数 Rotate,并返回用户旋转的角度。

用户应该能够在不了解检测过程的情况下使用这些组件。他们只需要关注检测到旋转后的逻辑。图 6 显示了为旋转检测器设计的块。函数 AddHandlerToCanvas 将检测器的监听器附加到画布组件,就像我们在 III-A 节中讨论的那样,以便用户可以在画布上执行手势。当检测到旋转手势时触发函数 Rotate,用户可以根据此函数返回的旋转角度确定应用程序的行为。

自定义手势检测

自定义手势由用户或程序员定义以供以后使用。使用自定义手势的一个例子是在游戏中,例如 Harry Porter。玩家可以执行不同的手势来施展法术以完成一些所需的动作。应用程序还可以使用自定义手势作为执行某些操作的快捷方式。

我们对自定义手势检测的实现涉及两个部分:1)如何添加用户定义的手势,以及 2)如何检测手势。

添加用户定义的手势

正如我们在 II-C 节中提到的,Android API 为我们提供了一个名为 Gesture Builder 的内置应用程序来添加手势,它将手势存储在二进制文件中,该文件可以由 GestureLibraries 类读取。但是,我们不希望用户在使用另一个应用程序时打开其他应用程序。为了使流程无缝衔接,我们使用了一个名为 Activity Starter 的 App Inventor 组件。

Activity Starter 是一个可以在应用程序内启动另一个应用程序的组件。为了使用它,用户需要安装这两个应用程序。要启动正确的应用程序,程序员需要使用正确的参数设置 Activity Starter,然后调用 StartActivity。图 7 显示了通过单击按钮启动 Gesture Builder 的示例应用程序。

图 7. 示例应用程序的块,单击一次按钮即可启动手势生成器。当屏幕初始化时,应用程序需要使用正确的手势生成器参数设置 Activity Starter。

在手势生成器中,用户可以通过提供其名称和形状来创建新手势。用户还可以重命名和删除现有手势。所有更改都将存储在用户手机 SD 卡上的二进制文件中。

检测用户定义的手势

要检测手势,我们需要先加载手势文件。 GestureLibraries 类中有一个内置函数,可以读取存储在用户 SD 卡中的二进制文件,并将其传输到 GestureLibrary 的实例中。每个存储的手势都是 GestureLibrary 中 Gesture 类的一个实例,并由其名称标识。输入的手势必须在 GestureOverlayView 类上执行,它将变成 Gesture 的一个实例。在 GestureLibrary 中,有一个名为“recognize”的函数,它将输入的手势作为输入,将其与库中存储的每个手势进行比较,并输出一个分数列表作为比较结果。分数越高,相似度越高。

要将此检测过程集成到我们的组件中,我们需要在 Canvas 对象顶部添加一个 GestureOverlayView。但是,当 Canvas 组件顶部有一个 GestureOverlayView 时,所有手指的移动都会用于预测执行了哪个手势,因此它会影响 Canvas 组件的其他功能。例如,用户可能希望在画布上绘图,并且仅在某些条件下使用自定义手势检测。因此,我们为用户提供了打开或关闭自定义手势检测的功能,以便用户可以在需要时启用手势检测,并在执行其他操作(如绘图和旋转)时禁用它。

当我们初始化自定义手势检测器时,我们使其具有与其附加的 Canvas 组件相同的大小和位置。要在 Canvas 组件顶部添加 GestureOverlayView,我们需要更改应用程序的布局。布局在 Android API 中定义,其中包含一组视图,程序员可以更改布局的配置以更改视图的位置。Canvas 组件本身是 Android API 中 LinearLayout 的一部分,很难在其顶部添加另一个视图,但此 LinearLayout 是 FrameLayout 的一部分,可用于我们的案例 [5]。

为了启用手势检测,我们将 GestureOverlayView 插入 FrameLayout,并将其堆叠在包含 Canvas 组件的 LinearLayout 顶部。在用户输入手势后,它将使用我们在 II-C 部分中讨论的过程来检测执行了哪个存储的手势。要禁用自定义手势检测,我们只需从 FrameLayout 中删除此 GestureOverlayView。

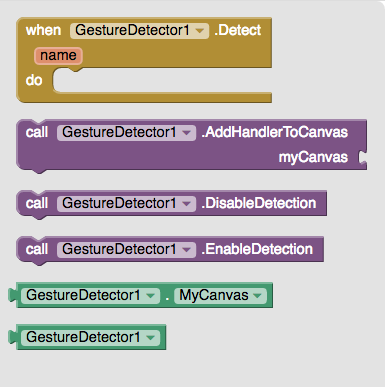

图 8. 手势检测器组件的块结构。屏幕初始化时调用 AddHandlerToCanvas 函数,将检测器与 Canvas 组件关联。用户执行手势时触发 Detect 函数,并返回一个字符串,该字符串是已识别手势的名称。如果未检测到手势,则返回的字符串为空。EnableDetection 和 DisableDetection 函数分别用于打开和关闭检测。

图 8 显示了手势检测器组件的基本块结构。屏幕初始化时调用 AddHandlerToCanvas 函数,将检测器与 Canvas 组件关联。在我们的组件中,用户不需要知道中间步骤,他们只关心执行手势后的操作,即存储的手势与输入的手势相对应时。因此,我们为用户提供了一个名为 Detect 的函数,当应用程序用户执行手势时触发该函数。Detect 函数为程序员提供了用户执行的手势的名称,该名称由存储的手势与输入手势相比的最高分数决定。但是,如果所有存储手势的得分都低于最低阈值,则输入手势可能不是存储手势中的任何一个。在这种情况下,该函数返回一个空字符串作为名称。这不会影响检测器的性能,因为手势生成器不允许将空字符串作为手势的名称。还有两个函数,分别称为 EnableDetection 和 DisableDetection。它们分别打开或关闭手势检测。当用户想要使用同一画布执行其他操作(例如绘图)时,他们需要禁用手势检测。当他们想要使用手势检测时,他们需要启用手势检测。

结果

我们通过将组件导入 App Inventor 的扩展服务器来测试它们。扩展服务器包含 App Inventor 扩展,但它仍在开发中,尚未向公众发布。我们为每个组件构建了两个示例移动应用程序来说明组件的用法并测试了它们的功能。我们与 App Inventor 组的学生一起测试了两个组件以了解它们的可用性,并使用测试结果将我们的组件的学习曲线与传统的基于文本的编程进行比较。

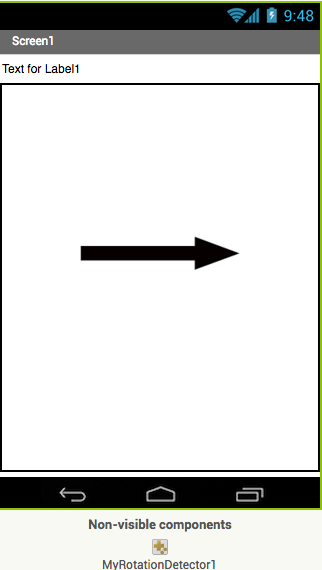

旋转检测示例应用

旋转检测器可用于旋转画布上的图像精灵。我们用它来旋转屏幕上的箭头图像。图 9 显示了示例应用的用户界面。标签显示箭头的当前方向。箭头是图像精灵,其方向可以通过两指旋转来更改。应用将根据检测器返回的旋转角度顺时针或逆时针旋转箭头。

图 10 显示了示例应用的块。屏幕初始化时,它会将画布附加到检测器。当检测到旋转手势并返回角度时,应用使用该角度来确定箭头精灵的方向。使用示例应用,用户可以用两根手指成功旋转箭头精灵。

图 9. 使用旋转检测器的示例应用的用户界面。标签显示箭头的当前方向,箭头精灵的方向可以通过双指旋转来更改。

图 10. 根据用户的手势旋转箭头精灵的示例应用的块。当用户顺时针旋转时,箭头的方向会增加;当用户逆时针旋转时,箭头的方向会减小。

自定义手势检测的示例应用

在本节中,我们展示了一个用于检测用户定义的自定义手势的示例应用。该应用允许用户添加、重命名和删除手势。当用户在画布上执行手势时,如果手势在库中,它能够检测到它并显示其名称。此外,用户可以打开和关闭检测。当检测关闭时,应用程序不应执行任何操作。

图 11. 使用自定义手势检测器的示例应用的用户界面。蓝色矩形是画布,标签显示检测到的手势的名称。画布下有两个按钮。“添加手势”按钮用于调用 Android API 提供的手势生成器应用,“启用检测”按钮用于打开/关闭手势检测。

图 11 显示了示例应用的用户界面。蓝色矩形是画布。用户可以在画布上执行手势,他们绘制的笔触是黄色的。可以通过单击“启用检测”按钮根据用户的需求打开或关闭检测。启用检测后,画布上所有手指的移动都被视为手势的一部分,并用于区分用户执行了哪种手势。禁用检测后,检测器将忽略用户的输入,用户绘制时不会显示黄色笔触。

图 12. 图 11 中设计的示例应用程序的块,用于检测自定义手势。初始化屏幕时,程序员设置参数以调用手势生成器应用程序,并将画布附加到手势检测器。单击“AddGesture”按钮时,应用程序将调用手势生成器应用程序。单击“启用检测”按钮时,它会切换手势检测的状态,并相应地将其打开或关闭。当启用手势检测并由用户执行手势时,将调用 Detect 函数。程序员使用 Detect 返回的名称来更改标签的内容。

图 12 显示了示例应用程序的块。程序员不需要知道如何检测手势,他们只需要关注手势检测后的操作。初始化屏幕时,程序员设置参数以调用手势生成器应用程序,并将画布附加到手势检测器。单击“AddGesture”按钮时,应用程序将调用手势生成器应用程序。单击“启用检测”按钮时,它会切换手势检测的状态,并相应地将其打开或关闭。当启用手势检测并由用户执行手势时,将调用 Detect 函数。程序员使用 Detect 返回的名称来更改标签的内容。

|

|

|

| (a) 添加手势 | (b) 检测圆形 | (c) 检测三角形 |

图 13。示例应用程序的屏幕截图。13(a) 是手势生成器应用程序的屏幕截图。它显示了库中的所有手势。13(b) 显示当用户绘制圆形时,应用程序检测到“圆形”,13(c) 显示当用户绘制三角形时,应用程序检测到“三角形”。黄线是用户执行的手势笔划。

图 13 显示了示例应用程序的屏幕截图。图 13(a) 是手势生成器应用程序的屏幕截图。单击“添加手势”按钮即可调用它,它显示了用户在其设备上定义的所有手势。图 13(b) 和图 13(c) 分别显示了圆形手势和三角形手势的检测。黄线是用户执行的手势笔划。

讨论

在本节中,我们讨论了我们在 MIT App Inventor 团队中对两个组件进行的测试调查,并讨论了我们组件的局限性。

测试调查

对于每个组件,我们在 MIT App Inventor 团队中分发了一份测试调查。参与者主要是在 MIT App Inventor 团队担任本科研究员的学生。他们拥有计算机科学和 Android 编程背景,并且知道如何使用 App Inventor 及其扩展。

我们要求他们实现我们在第四部分中展示的每个组件的示例应用程序,并提供详细说明。在调查结束时,我们询问完成每个应用程序需要多长时间,以及使用我们的组件完成我们给他们的任务是否容易。每个应用程序的平均时间为半小时,大多数学生都同意我们的组件易于使用,并提供说明。即使考虑到学习 App Inventor 所花费的时间,与传统的基于文本的编程相比,使用我们的组件创建涉及多点触摸手势和自定义手势检测的应用程序对于新手程序员来说也要容易得多。

局限性和未来工作

我们的自定义手势检测使用 Android API 对用户执行的手势进行分类。在测试期间,我们发现 Android API 在多笔划手势方面表现更差,即使它允许多笔划手势。此外,手势存储为手指运动的轨迹。因此,顺时针和逆时针画圆是两种不同的手势,即使它们的形状相同。

一种潜在的可能性是开发我们自己的手势识别算法以满足特定需求,但这对新手程序员来说不是必需的。

结论

在本文中,我们扩展了 MIT App Inventor,添加了两个扩展组件:1)旋转手势检测器和 2)自定义手势检测器。我们的贡献包括 1)设计模块、2)实现和测试、3)以及为每个组件创建示例应用程序、教程和文档。我们发现,对于新手程序员来说,使用 MIT App Inventor 和我们的扩展组件创建涉及多点触摸手势和自定义手势识别的应用程序更容易。

本文系谷歌翻译,原文点此。

扫码添加客服咨询

扫码添加客服咨询